Did you know that New York City banned pinball for over 30 years?

Surprising as it may seem, there was a time and place when pinball was not a welcome site across towns and cities in the United States.

It was dangerous. It was something Vile. It was corrupting the youth. It was a panic.

On today’s episode, we are going to talk about a moral panic that predates video games, heavy metal, and Dungeons and Dragons.

Today we take a look at when pinball was banned, for 30 years, in the Big Apple.

Pinball Panic: The New York City Pinball Ban

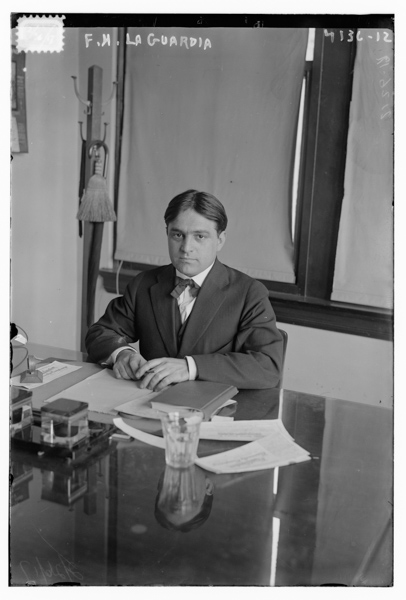

Why did New York city ban pinball? Well, let’s talk a little bit about the political landscape first, and the man who facilitated the ban, New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia.

Prof. Greaney: There’s a difference, in my opinion, I think most people would agree, between a politician and a public servant.

And I think someone like La Guardia, and even the Roosevelts, both of them, were public servants before they were politicians.

Joe Greaney is a professor of history at Lynn University.

Prof. Greaney: 99th mayor of New York. He was born in New York City. His father was Italian. His mother was Jewish.

From that, he had picked up fluency in Italian from his father and Yiddish from his mother, along with Croatian, so we was a linguist, too.

Prof. Greaney: When he was a young kid, he had to move to Arizona, where his father was a band leader at Fort Whipple, which is in Prescott, Arizona, so he got a lot of his education there.

Prof. Greaney: … he worked in the United States State Department in a number of different posts where he served at the Consulate in places like Budapest, which was part of the Austrian Hungarian empire at the time. [Twist 00:00:55], where his mother was actually from.

Prof. Greaney: He was elected to the United States Congress in 1916. So he got inaugurated on, or sworn in, as a Congress member in March of 1917, but the month later, the United States entered World War I, so he resigned from the Congress and served as a major, eventually as a major, in the United States Army Air Corps, which was the precursor of the United States Air Force.

Prof. Greaney: …he went back to the United States after the war, served in Congress for about eight years. Eventually he was defeated in 1932, obviously because of the depression and things like this. Most Republicans lost in that election year. And then decide the next year to run for Mayor of New York, which he won.

Prof. Greaney: So a progressive Republican sort of like in the theater Roosevelt tradition and the number one thing Progressive’s wanted to do was they wanted to reform city, government, especially machine politics.

Prof. Greaney: Also, Progressives felt at an important part of society of the time because of a large number of immigrants coming to the United States at that time, the importance of assimilation. And how do you assimilate people into American culture? Education. So that’s why people like La Guardia, Theodore Roosevelt, later on Franklin Roosevelt, really pushed for education, especially at younger ages.

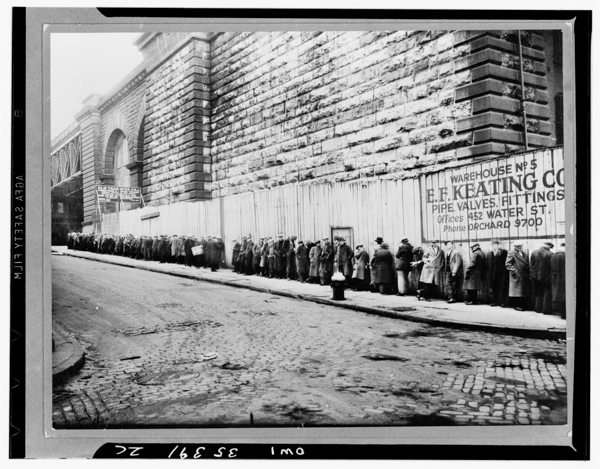

LaGuardia was elected mayor in the midst of the great depr

ession, which hit New York especially hard.

Prof. Greaney: When he became mayor, the United States was right in the midst of the Great Depression, so you probably had everything that went along with that, things that you’ve seen, like kitchens and bread lines and all kinds of things like this, and literally millions of people out of work.

And New York City has always been the important commerce center of the United States since they built the Erie Canal in the 1820s, it’s been the number one city of the United States and now the world and stuff like that.

Prof. Greaney: So all the problems the United States had during the Great Depression were magnified in New York.

Pinball, Burlesque, Vaudeville, these were all past times that the people of New York use to distract from the Great Depression. Bagatelle was a precursor to pinball that dated back centuries. By the early 1900s, the game looked very similar to pinball, to the point that in some news articles the terms pinball and bagatelle were used interchangeably.

Concerns over bagatelle, pinball, and their relationship to gambling pre-date LaGuardia. For example, in 1933, a Harlem man named Bejamin Chester was arrested for gambling on bagatelle. However he was able to escape punishment in a demonstration in front of the court to show that bagatelle was a game of skill, not chance. An officer of the court set a high score, and Chester beat the score.

A similar story happened the following year, when a shop keeper had to beat a high score set by an officer of the court.

A few years into Laguardia’s first term, a man named Arthur Ryan, the chief of the Dyker Civic Association, wrote a letter to Mayor Laguardia asking for help in protesting the “evil” of pinball.

Ryan wrote the letter after collecting the complaints of mother’s who were worried that their children were spending too much time playing pinball and losing their lunch money.

Three days later, LaGuardia and Commissioner Moss banned pinball and bagatelle games that give prizes to save the nickles and dimes.

Game owners scoffed and pushed back, filing to the court for a writ of mandamus against the comissioner.

Prof. Greaney: He had to Make sure that people were doing things that he felt were appropriate.

Prof. Greaney: Any time you try to regulate behavior, you usually end up having these problems. It sounds like such a silly thing, but what parent in the United States today can be happy thinking that their kids spending 10 hours a day playing video games? It’s the same thing.

Prof. Greaney: Now we’re not going to pass laws, obviously, about that. But I guess some people at that time thought because it was a public place, the pinball was in a public place, you can’t put a pinball in a bedroom.

I guess you could, but most people can’t, that they wanted their children to be doing things… Remember I told you before. Education. Things that are important. Things that are going to help them grow.

Pinball was quite lucrative at the time. In this article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle it mentions that the pinball industry in Brooklyn took in about 20 million dollars in 1935 across 16,500 machines. That is approximately 350 million dollars in today’s money.

The ban spurred was upheld in the Manhattan Supreme court in February of 1936. The scope of the decision left the operation of pinball machines were lawful as long as no prizes were given an no amusement was sought.

In August of 1936, LaGuardia, Police Comissioner Valentine, and the District Attorneys made a big event of taking a tug boat out to the Long Island Sound, where they dumped confiscated weapons, and gambling devices including pinball machines, into the water.

By the end of 1936, police officers were arresting any pinball machine owners that had not acquired an amusement license.

Six years later, LaGuardia got what he sought. In December of 1941, LaGuardia had asked the city council to pass a law, banning pinball outright. Ultimately though he wouldn’t need any legislation. Magistrate Ambrose Haddock banned pinball in late January of 1942, by ruling that:

“Even if the player does not get paid off for winning…the machine is designed for gambling, therefore the possibility for gambling is always present. Second, even if the player’s amusement is the only motive for playing, that amusement is a thing of value which is being exploited.”

In short, amusement was enough of a prize for New York to ban pinball.

At noon, under the orders of Mayor LaGuardia, on the day the ruling was made, plainclothes police officers drove around the Bronx in trucks grabbing every pinball machine they could find and issuing summonses to the owners.

Pinball operators attempted to collect any machines they could off the street, because at the time, Pinball machines were not in production so that the supplies could be used to support the war effort.

About 647 candy and cigar stores were raided in Brooklyn as well and within a week, $3000 were collected from the pinball mahines were taken and added into the police pension fund. That’s the equivalent of $50,000 in today’s money.

Within two weeks nearly 3200 pinball machines had been confiscated. Approximately 1 ton of them had been scrapped, and court summonses had been issued to 1624 store owners.

Unlike other panics, where the waxing of morality by politicians often didn’t lead to much, this one did. The people of New York took notice.

There were two letters to the editor published in the New York Daily news the following week.

The first was written by a man named Victor Eshreff, who sarcastically congratulated the police in their efforts, and mentioned that they should now round up the people catch all the outlaws who toss coins or play gin rummy.

Another letter was written by a pinball operator, who had lost his job because of the ban. Then, a few months later, another letter is published, this time by a candy shop owner, who feared he would have to close down after the absence of his pinball machine dried up all his foot traffic.

In October of 1942, LaGuardia gifts the Commandant of the City Patrol new batons made out of the legs of confiscated pinball machines. More than 2000 clubs were made.

LaGuardia would then state to the press that pinball was, “A real larceny machine, brother of the tinhorn… the main distributors, wholesalers and manufacturers are slimy crews of tinhorns, well-dressed and living in luxury from this penny thievery.”

LaGuardia was proud of his accomplishment, toting it several times on his radio show. In May of 1942 he said: “Police Department announced with pardonable pride that it had cleaned up the pinball racket. Yes, sir, we cleaned it out. Thousands of those larcenous gambling machines were seized and destroyed and some, yet to be destroyed put in the custody of the Police.”

In October of 1942, LaGuardia gifts the Commandant of the City Patrol new batons made out of the legs of confiscated pinball machines. More than 2000 clubs were made.

LaGuardia would then state to the press that pinball was, “A real larceny machine, brother of the tinhorn… the main distributors, wholesalers and manufacturers are slimy crews of tinhorns, well-dressed and living in luxury from this penny thievery.”

While the New York City ban on pinball machines wasn’t undone until 1976, it’s important to point out that it was no sooner than the next administration that enforcement on the ban started to be relaxed. In 1947, during the O’Dwyer administration, there was already talk of lifting the ban, and the news paper article mentions that people had already started to be more brazen in the placement of pinball machines.

In April of 1976, Pinball historian and GQ writer Roger Sharpe performed a demonstration in front of New York City Council. The demonstration show ed as Benjamin Chester demonstrated in 1933, that they were indeed games of skill, and not games of chance. The following month, New York legalized pinball.

Even then it wasn’t unamious. Councilman Leon Katz, leading the dissenters said:

“Mobsters and racketeers will use the profits of these machines to launder dirty money from prostitution, drugs, and gambling.”

Well you can’t please everyone.

The pinball panic wasn’t just n New York at this time, but happened in cities across the country. I believe though that this is an example of a moral panic that just happened in a perfect storm of moralistic leaders, and the great disruption of World War II.

By the following year, in 1977, nearly 10,000 new machines could be found around the city and to this day, most of the arcades that are still around feel incomplete without a pinball machine.